– Dr Disha Gupta, Dubai

Abstract

Extraoral sinus tracts of dental origin continue to be a diagnostic challenge. They are frequently misdiagnosed as lesions of non-odontogenic origin. This is a case report of a patient complaining of extraoral draining sinus since 6 months who visited many medical practitioners. Radiographical investigation showed large periapical lesion associated with root canal treated mandibular 1st molar. Chronic infection of a tooth can drain through a sinus tract, which may be intra-oral or extra-oral. Dental symptoms are not always present or may be missed by patient and this confuses the clinical picture. which can lead to misdiagnosis of the current condition. Timely dental treatment can resolve the condition and with this case report, we can highlight the importance of dental consultation in these situations.

Introduction

A sinus tract is a communication between an enclosed area of inflammation/infection to an epithelial surface or body cavity. The main etiology of extraoral sinus tracts is chronic dental infection. As a result of misdiagnosis, patients may be subjected to unnecessary and ineffective treatment such as repeated courses of antibiotics, multiple biopsies, and surgical excision of the cutaneous lesion. This brings only a temporary resolution of the lesion and once the effect is gone, it reoccurs. When the source of odontogenic infection is eliminated, healing of the sinus is expected within 7 to 14 days.

Clinical presentation of an extra oral sinus – The extra-oral draining sinus typically presents as an erythematous nodule with crusting or ulcer over the skin which drains pus periodically. It is characterized by 'dimpling' or retraction below the normal skin surface. It is usually possible to palpate a cord-like tract that attaches to the underlying alveolar bone in the area of the suspected tooth. Symptoms from the teeth may only present in 50% of patients, the involved tooth is always non vital but may not always be tender to percussion.

This is a case report of a patient complaining of extraoral draining sinus since 6 months who visited many medical practitioners. Timely dental treatment resolved his condition.

Case Report

A 15 year old boy reported with the chief complaint of pus discharge from the right lower jaw region since 6 months reported to the clinic. A draining sinus tract was present extra orally (Fig 1).

For the treatment of extra oral abscess, the patient visited many dermatologists. Initially, the condition was misdiagnosed as infected sebaceous cyst. Antibiotics were prescribed followed by incision and drainage. Even after 6 months, the drainage could not be controlled.

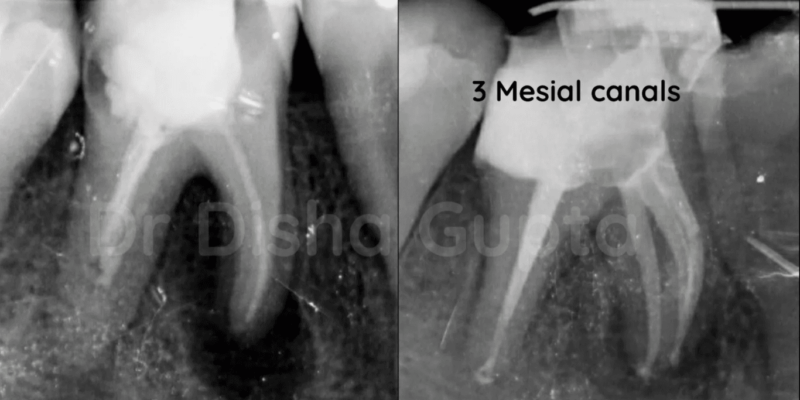

Meanwhile patient was scheduled for pending orthodontic braces consultation. Intra orally, there was a grossly decayed mandibular right first molar tooth with grade 1 mobility & fractured restoration. Periodontal probing around the tooth revealed pocket depth within physiological limits with no intraoral sinus. Radiographic evaluation (panoramic and intra oral periapical) and sinus tracing (x-ray) revealed associated periapical infection of root canal treated right mandibular first molar along with missed mesial canals and short obturation in distal canal (Fig 2a, Fig 2b). TOP test was negative. Dental history revealed that RCT was performed 3-4 years back.

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for this case was:

- previously RC treated tooth with chronic apical abscess and extra oral sinus tract

- osteomyelitis

- actinomycosis

- foreign body

- local skin infection

- pyogenic granuloma,

- salivary gland and duct fistula

- suppurative lymphadenitis and

- neoplasm among others.

Based on the clinical and radiographic examinations, a final diagnosis of previously RC treated tooth with chronic apical abscess and extra oral sinus tract was made.

Nonsurgical re-endodontic treatment of the tooth was scheduled.

Treatment

Patient was scheduled for Re-RCT of mandibular 1st molar. Decoronation was done followed by removal of gutta percha from mesial and distal canals. Five root canals, namely the mesiobuccal (MB), mesiolingual (ML), distobuccal (DB), distolingual (DL) and the quite rare mid mesial (MM) canal, were located under a dental operating microscope (DOM) (Fig 3).

Mid mesial canal plays a very important role in these cases, one missed canal can further complicate the case and leads to non-healing of the extra oral sinus along with periapical lesion.

Chemo mechanical preparation done using saline, 3 % NaOCl and 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate solution (after thoughly flushing the canals with saline or water). Canals were then shaped using Protaper Gold files. The canals were then dressed with water based calcium hydroxide paste (Ultracal). Cleaning, shaping and filling of the root canal and periradicular region determine the success of the treatment and good periradicular healing. The sinus tract was treated with H2O2 irrigation along with povidine iodine solution to remove the dead necrotic tissue of the tract and facilitate healing.

Patient was recalled after two weeks, no more suppuration from the sinus tract was observed with spontaneous closure of the tract (Fig 4).

The interim dressing was changed every two weeks for 2 months. During this period, the patient remained asymptomatic; meanwhile upon radiographic investigation the periapical area showed signs of excellent healing and bony recovery. Subsequently, the root canal obturation with gutta-percha points and bio ceramic sealer was performed (Fig 5).

Discussion

Sinus Tracts

A sinus tract prevents swelling or pain from increased pressure because it provides drainage from the primary odontogenic site. Symptoms from the teeth are present only in 50% of patients, which could explain why patients frequently consult with a physician first for help. Mostly in such cases, delay in the diagnosis often leads to unnecessary antibiotic treatment and surgical intervention. Intervention must start with an intensive medical and clinical history, and odontogenic infection must be borne in mind in the differential diagnosis of such lesions on the face or neck. Hence, the clinician should pay extraordinary attention to oral clinical conditions, such as caries, deficient restorations, and periodontal conditions.

How do extra -oral sinus tracts form? – Sinus tracts of dental origin may be misdiagnosed due to lack of dental history provided by patient. If a draining lesion is seen on the facial or cervical area, a dental origin should be considered a priority in differential diagnosis. Other etiologies consist of pyogenic granuloma, foreign body reaction, deep fungal infection, squamous cell carcinoma, and osteomyelitis. Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tracts typically arise from periapical infections around the root apices as a result of pulpal necrosis, nearby caries or traumatic injury. This chronic process slowly evolves through the cancellous alveolar bone, following the path of least resistance until it perforates the cortical plate of the mandible. Cutaneous fistulas then arise from the spread of infection into the surrounding soft tissues. Sometimes the location of the sinus tract opening does not necessarily indicate the origin of the inflammatory exudate, tracking of the sinus tract with a gutta-percha point contributes to the final correct diagnosis.

Tracking a sinus tract – Tracing a sinus tract is an amazing diagnostic tool since it will trace right to the source of the infection and the culprit tooth. Take a size 25 gutta percha and put it right through the sinus tract until it stops. Sometimes, you may need to use a periodontal probe to create a glide path before you place gutta percha. The patient need not be anesthesized during this procedure unless he has pain. Shoot an x-ray to see where the gutta-percha leads to.

Radiographic interpretation is very important for the diagnosis. In this case, panoramic radiography showed a periapical radiolucency associated with the affected tooth, in which root canal treatment was attempted. Sinus tracing showed the exact culprit tooth.

What to do with a sinus tract? A proper consultation should be made by the treating dentist to explain the pros and cons of the treatment. Explain the prognosis with re-treatment of endodontic therapy and why it was failed at first place. Give options of extraction and further replacement of the tooth.

Eradication of the original source of infection is most important for the treatment by means of non-surgical RCT. In this case, prominent reduction of the abscess after nonsurgical RCT was observed. Automatic closure of the tract should be anticipated within 5 to 14 days after RCT. Excision of the sinus tract is not recommended, as most authors believe that the tract will heal once the primary cause is removed. Eventually, in this case, the lesion on the cheek recovered entirely leaving only a slight hyperpigmented region, and the periapical lesion healed on the radiographic examination.

Mid-mesial canals

Comprehensive learning of both normal and abnormal root canal morphology can play a crucial role in outstanding endodontic treatment as in this case mid mesial (MM) canal plays an important role. MM canals have been described as having a small orifice deep within the isthmus or a developmental groove between the two orifices of the MB and ML canals. The inability to locate, debride or fill all canals of the root canal system has been a major cause of post-treatment failure. Azim et al, in a February 2015 JOE article wrote about the incidence of mid-mesial canals in lower molars. The authors found that in the 91 molars evaluated, 6 (6.6%) teeth had mid-mesial canals that could be located without troughing of the axis defined by the orifices of the MB and ML canals. Following troughing, a further 36 (39.6%) mid-mesial canals were found with 60% occurring in the second molars. Of the 42 mid-mesial canals found, 4 (9.5%) had a separate coronal and apical orifice, i.e. were a completely separate canal. In the remaining teeth, the mid-mesial canals joined either the MB or ML canal prior to the apical terminus.

What is a mid-medial canal? The mesial root canals of the first and second mandibular molars do not present a consistent pattern. MM canal, whose orifice is, in general, disclosed, is sometimes located as an intermediate canal in the developmental groove connecting a mesiobuccal (MB) canal and a mesiolingual (ML) canal. In 1974, Barker et al report the fifth canal with an independent middle mesial canal in the mandibular first molar; this report was followed by a similar finding by Vertucci and Williams. Various published articles on the presence of a MM canal in Europeans, Asians, Africans, and South/North American populations, show that the incidence of a mandibular second molar with a MM canal ranges from 0% to 12.8%. Pomeranz et al in 1981, classified MM canals into three types as follows:

- fin – allowing free instrument movement between the main and accessory canal;

- confluent- having a separate orifice but merging more apically with the MB or ML canals; and

- independent –having a separate orifice and apical terminus.

How to locate MM canal? Troughing technique may enhance the chances of locating MM canal, it is safe and effective for the negotiation of MM canals. In brief, troughing technique requires minimal dentin removal between the MB and ML canals in a mesio-apical direction away from the furcal danger zone. Troughing at that level requires clear visibility, specialized instruments of small size like munce discovery burs, and caution to avoid strip perforation by using ultrasound tips or long-shank round burs under the operating microscope. Several authors have suggested that a troughing preparation with a depth ranging between 0.7 and 2.0 mm is adequate.

A lot of authors have agreed on the presence of three foramina in the mesial root, very few have reported presence of three independent canals. CBCT has been very successfully used in endodontics for a better understanding of root canal anatomy and evaluation of root canal preparation and vertical fractures.

Conclusion

In the presented case report the healing of the atypical sinus tract associated with periapical lesion was observed. We can conclude that:

- Proper diagnosis is the key of success in extra oral sinus cases.

- A careful oral examination is mandatory prior to the final diagnosis.

- It is important that physicians have an awareness that a cutaneous lesion of the face and neck could be of dental origin and should always seek a dental opinion.

- Elimination of the dental source of infection results in resolution of the sinus tract without the need for surgical excision and long-term unacceptable aesthetic results.

- Locating extra canals, especially in cases of re-RCT is a must.

References

- Cohenca N, Karni S, Rotstein I . Extraoral sinus tract misdiagnosed as an endodontic lesion. J Endod 2003; 29: 841–843.

- Johnson B R, Remeikis N A, Van Cura J E . Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous facial sinus tracts of dental origin. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130: 832–836.

- McWalter G M, Alexander J B, del Rio C E, Knott J W . Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental aetiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1988; 66: 608–614.

- Lewin-Epstein J, Taicher S, Azaz B . Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Arch Dermatol 1978; 114: 1158–1161.

- Gorsky M, Kaffe I, Tamse A . A draining sinus tract of the chin. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1978; 46: 583–587

- Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract associated with a mandibular second molar having a rare distolingual root: a case report Article number: 13 (2015) J Clin Diagn Res. 2013 Jun; 7(6): 1247–1249.

- Management of an Endodontic Infection with an Extra Oral Sinus Tract in a Single Visit: A Case ReportVertucci F, Williams R. Root canal anatomy of the mandibular first molar. J NJ Dent Assoc 1974;45(3):27-28.

- Goel NK, Gill KS, Taneja JR. Study of root canals configuration in mandibular first permanent molar. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 1991;8(1):12-14.

- Pomeranz H, Eidelman D, Goldberg M. Treatment considerations of the middle mesial canal of mandibular first and second molars. J Endod 1981;7(12):565-568.

Comments