– Dr Sonal Yerpude

Abstract

Orofacial pain is one of the key considerations for diagnosis in routine dentistry. We all are familiar with patients demonstrating referred pain in our practice. The pain can be referred from a tooth or muscle or any other site from the body to an area which shows no clinical or investigative findings. Such situations are tricky to diagnose and a thorough investigation is the key to success for such cases. The article demonstrates a case report under the guidance of Dr. Davis Thomas. When a patient comes with pain around certain teeth but clinical or radiographic findings are contradictory to the patients chief complaint, ‘diagnostic blocks’ act as a very simple yet effective way for diagnosis of site or the source of pain .

Introduction

To be able to differentiate between the site and source of the pain should be one of the key criteria for diagnosis. Site of pain is the spot or area where the pain is felt, it may or may not be the place where the pain originates. It is easily pointed out by the patient. Source of pain is the spot from where nociceptive input of the pain originates. For a good clinician to be able to achieve correct diagnosis and treatment plan, the source of pain has to be identified.

When the site and source of pain is the same, diagnosis and treatment is easy. But when they differ, like in cases if referred pain, diagnosis and treatment can be extremely tricky, time consuming and challenging.

A very useful and effective technique for the diagnosis in such situation would be diagnostic blocks. An anaesthetic block at the site of pain will immediately cut or cease the painful stimulus and the pain will stop in case of primary pain. In case of referred pain, the anaesthetic agent will not cease the pain at the site of pain.

Case report

A 24 year old Indian married working lady reported with sharp shooting pain in upper right premolar region since two weeks. Pain aggravated on chewing food and while talking. Intensity of pain was more profound in evening and patient self medicated herself with NSAID’s which reduced the pain intensity in 10-20 min for 10-12 hours .

When the patient walked in to the practice, she had throbbing pain for the past 2 hours .

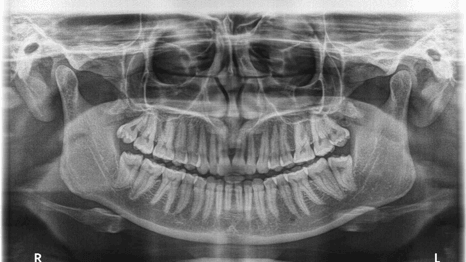

On intraoral and radiographic examination, there was no cause of pain to be actually originating from the premolar region .

With patients consent, 1.2 ml 2% lignocaine hydrochloride was injected in the buccal and palatal area of pain site. As was expected, the anaesthetic agent did not cease the pain at all.

We recalled the patient when she is symptomless. On provocation of middle temporalis muscle, patient gave very positive replication of pain with same intensity and temporal pattern, as it acted as trigger.

Differential diagnosis for this case –

- Pain referred from other teeth (odontogenic)

- Pain due to trauma to some muscle or ligament

- Sinus congestion

- Systemic involvement

Discussion

Evidence has shown the that the three divisions of temporalis muscles refer pain to maxillary teeth and TMJ on the same side. The thorough knowledge of myofascial pain referral and various treatment options for non odontogenic orofacial pain is the key to successful diagnosis and treatment planning.

The key element in this particular case was that the diagnostic block clearly indicated that the area around the premolars is the site of pain and not the source of pain.

When the patient walks in to your practice, he will point to the area or site of the pain . At times the diagnosis is clear when site and source of pain is similar and can be corelated by clinical and radiographic findings. The actual complication arises when the site of pain mentioned by the patient is not corresponding with any clinical diagnostic test such as pain on percussion, thermal testing, or radiographic findings. At any given point, we should be able to replicate the pain by stimulating the patient’s site of pain – this will achieve correct diagnosis. If the pain is not replicated we must think of an alternate source of pain .

- When the site and source of pain is similar it is called as primary pain. Eg. acute irreversible pulpitis in #11 and pain felt around #11 buccal mucosa.

- The situation where the site and source of pain differ in location is known as heterotopic pain. eg pain in SCM muscle felt in preauricular region on the same side.

Heterotopic pain can be –

- Central pain, when the pain is originated by structures of CNS and felt in peripheral structures of the body.

- Projected pain, is heterotrophic pain felt in the exact anatomical distribution of the major nerve trunk.

- Referred pain, is felt in areas innervated by different nerves from one that mediates the primary nociceptive inputs, where the pain is totally dependent on the stimulation of the original source of pain.

Treatment provided at the site of pain in case of heterotopic pain, where the pain source is located at a different position, can result in an absolute annoying result for patient as well as the dentist. This is where diagnostic blocks can play a role.

There has been enough evidence that the convergence of afferent impulses among CNS interneurons takes place in Trigeminal spinal track nucleus. The three branches of trigeminal nerve V1, V2, & V3 have shown evidences of referral pattern.

Understanding the terminal lamination pattern and convergence of trigeminal nerve is not in the objective of this article. Here are few tips to follow for referral pattern nerve by grouping pattern-

- Incisors refer pain to incisors and molars to molars.

- The reference pattern rarely crosses the midline unless pain is originated in the midline.

- The pain when felt outside the nerve innervation it is always felt upwards to the nerve (toward the head). Eg pain originating from cervical region is felt in the TMJ or jaw but rarely in the thoracic region.

Conclusion

During clinical situations where there is no conclusive findings radiographically or clinically at the site of pain, diagnostic block can help identify if the site of pain is also the source of pain.

Acknowledgement

The Diagnostic Block crucial clinical tip which has helped in diagnosis of many non odontogenic clinical cases has been an integral part of our orofacial pain practice under the guidance of Dr. Davis Thomas and constant insights from my fellow batchmates and family.

References

- Okeson JP. Psychologic factors and oral and facial pain. Bell’s oral and facial pain 7th ed.

- Wolff HG, Wolf S. Pain. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1958.

- Fields HL. Pain. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1987.

- Wolff HG, Hardy JD. On nature of pain. Pain Res 1947:27:167-179

- Chandler MJ, Qin C, Yuan Y, Foreman RD. Convergence of trigeminal input with visceral and phrenic inputs on primate C1-C2 spinothalamic tract neurons. Brain Res 1999;829:204–208.

- Milne RJ, Foreman RD, Giesler GJ. Viscerosomatic convergence into primate spinothalamic neurons: An explanation for referral of pelvic visceral pain. In: Bonica JJ, Iggo A, Lindblom U (eds). Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. Vol 5: Proceedings of the Third World Congress on Pain. New York: Raven, 1983:131–137.

- Sessle BJ. Neural mechanisms and pathways in craniofacial pain. Can J Neurol Sci 1999;26(suppl 3):S7–S11.

- Sessle BJ, Hu JW, Amano N. Convergence of cutaneous, tooth pulp, visceral, neck and muscle afferents onto nociceptive and nonnociceptive neurons in trigeminal subnucleus caudalis (medullary dorsal horn) and its implications for referred pain. Pain 1986;27:219–235.

Comments