Overcoming Root Canal Failure: Endodontic Failure

Endodontics is the bread and butter of general dentistry. Relieving a patient in pain is the main aim of every dentist; when this effort fails, it can result in disappointments and fear of Root Canal Treatment failure requires analysis and reconstruction. After all, all failures are not permanent, can be prevented and sometimes, corrected. Let us face our fears and analyse endodontic failure in detail.

Etio-Pathogenesis of Endodontic Failure

I. Factors prior to RCT

- Incorrect diagnosis

- Technical difficulties

- Vertical root fracture

- Systemic diseases

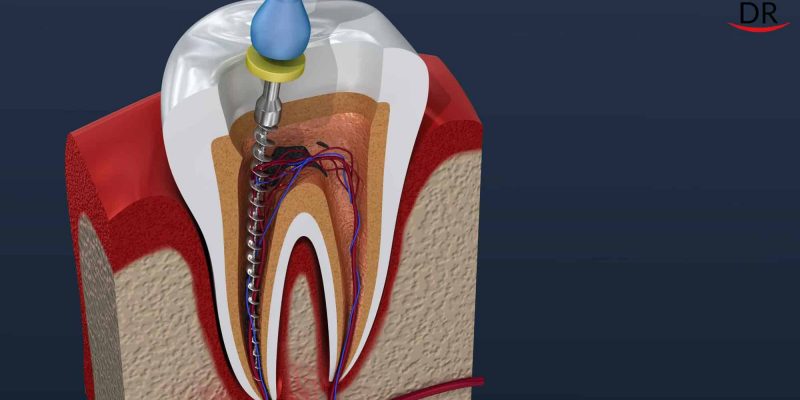

II. Factors during RCT

- Anatomical variations

- Missed canal

- Ledge formation

- Infections

- Poor debridement

- Mechanical and chemical irritants

- Incomplete access preparation

- Incorrect working length determination.

- Improper obturation

- Overfilling of root canals

- Furcation perforations

III. Factors post RCT

- Failure following treatment

- Failure following surgical treatment

IV. Miscellaneous

- Nerve paresthesia

- Tissue emphysema

- Instruments aspiration and ingestion

Diagnosis of Endodontic Failure

The most accurate determinations of healing and nonhealing are based on signs and symptoms, radiographic and histologic examinations.

Clinical Examination: Signs and/or symptoms, if marked and persistent, are probably indications of disease and failures. Persistence of adverse significant signs (e.g., swelling or sinus tract) or symptoms (e.g., spontaneous pain, dull persistent ache or mastication sensitivity are considered in diagnosing a failure.

Radiographic Findings: The importance of radiographic evaluation in determining endodontic success or failure cannot be overemphasised. It is a universal tool in the assessment of treatment results without which no claim of success could be justified. Since the radiographic evaluation plays a basic role in the assessment of treatment results, any fallibility associated with the interpretation of radiograph directly distorts the reported rates of success and failure. It is important to remember that complete bone formation in periapical lesions may take 6 months to a year. It is advisable to store pre and post operative radiographs for comparisons of size of lesions to distinguish between healing lesions and formation of new lesions. This will help avoid false positive diagnosis.

Histologic Examination: Routine histologic evaluation of periradicular tissues after root canal treatment is impractical and not possible without surgery. If treated tooth were to be evaluated histologically, successful treatment would be indicated by reconstitution of periradicular structures and an absence of inflammation.

Criteria for Case Selection in Endodontic Failure

The purpose of case selection is to determine the feasibility and practicality of treatment, so as to avoid treating cases that will fail regardless of the quality of treatment.

Diagnosis: The presence or absence of periradicular disease is determined according to clinical and radiographic findings. Differential diagnosis of non-endodontic disease is also considered.

Selection of Treatment: Currently, the patient ultimately selects the treatment, based on information communicated by the clinician. So the responsibility of communication of correct, precise information listing down risks vs benefits in simple, understandable terms and language is solely on the dentist.

Treatment of Existing Disease: Post-treatment disease definitely requires intervention, even when symptoms are absent. When treatment is preferred over extraction, re-treatment and apical surgery should be considered for both. Comparing the two modalities, retreatment offers a greater benefit and better ability to eliminate the disease’s etiology (root canal infection) with minimal invasion and a smaller risk such as significantly less postoperative discomfort and a lesser chance of injuring nerves, sinuses or other structures. Therefore, case selection is based on patient, tooth and clinician considerations that either preclude retreatment or restrict its feasibility in a way that decreases the potential benefits and increases the potential risks; the modified benefit-risk balance may not outweigh that of apical surgery. In combined endo-perio lesions, it is important that this diagnosis is established first and endodontic treatment should be followed by scaling, root planing and if necessary, flap surgery.

Endodontic Mishaps and their Prevention

1. Improper Diagnosis: Root Canal Failure

Incorrect oral examination leading to incorrect diagnosis is usually due to a misinterpretation of pain, vitality test and radiographs.

Recognition: The wrong tooth that has been treated is sometimes a result of re- evaluation of a patient who continues to have symptoms after treatment.

Correction: Treating the wrong tooth includes appropriate treatment of both teeth i.e.; the one tooth incorrectly opened and the one with the original pulpal problem.

2. Missed Canal: Root Canal Failure

Some canals are not easily accessible or readily apparent from the chamber.

Recognition: Missed canals occur during or after treatment. During treatment, an instrument or filling material may be noticed not exactly centered in the root, indicating that another canal is present. Radiographs with different angulations may help determine presence of additional canals.

Correction: Retreatment is appropriate and should be attempted before recommending surgical correction.

3. Access cavity perforations: Root Canal Failure

One of the irreversible complications of endodontics is perforation into the furcation area in posteriors or labial area in anteriors while gaining access to pulp chamber of tooth.

Recognition: If the access cavity perforation is above the periodontal attachment, the first sign of the presence of an accidental perforation will often be the presence of leakage, either saliva into the cavity or sodium hypochlorite out into the mouth, at which time the patient will notice the unpleasant taste. Unnatural amount of bleeding, intense pain, difference in tactile touch and radiographs with files can also help recognise perforations.

Correction: Several materials have been recommended for perforation repairs such as cavit, amalgam, calcium hydroxide paste, super Ethoxy-Benzoic Acid (EBA), glass ionomer cement, gutta-percha, tricalcium phosphate or hemostatic agents such as gelfoam and Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA) which has shown convincing results in apical cavity perforations.

4. Apical perforations: Root Canal Failure

Perforations in the apical segment of the root canal may be the result of file negotiating a curved canal or not establishing accurate working length and instrumenting beyond the apical confines. A paper point when inserted to the apex, will confirm a suspected apical perforation.

Recognition: An apical perforation should be suspected if the patient suddenly complains of pain during treatment, if the tactile resistance of the confines of the canal space is lost. A paper point inserted to the apex and a radiograph showing file extrusion beyond apex will confirm a suspected apical perforation.

Correction: Effort to repair apical perforations maybe to attempt to renegotiate the apical canal segment or to consider the perforation site as the new apical opening and then decide what treatment the untreated apical root segment will require.

5. Crown Fractures: Root Canal Failure

The tooth may have a preexistent infarction that becomes a true fracture when the patient chews on the tooth weakened additionally by an access preparation. Such fracture is usually recognised by direct observation.

Correction: Crown fractures usually have to be treated by extraction unless the fracture is of a “chisel type” in which only the cusp or part of the crown is involved; in such cases, the loose segment can be removed, and treatment completed. Full crown coverage post RCT becomes mandatory in such cases.

6. Separated Instruments: Root Canal Failure

Limited flexibility and strength of intracanal instruments combined with improper use may result in an intracanal instrument separation.

Recognition: Removal of small size file with a blunt tip from a canal and subsequent loss of patency to the original length even after repeated irrigation & recapitulation are the main clues for the presence of a separated instrument.

Correction: The optimal correction of instrument fracture or the presence of other foreign objects in a canal is to remove the obstruction. Ultrasonic fine instruments have proven most effective in loosening and ‘flushing out’ broken fragments. Using microscopy and special fine diamond tips a tunnel can be created around the separated instrument, which can then be vibrated and dislodged.

7. Canal Blockage: Root Canal Failure

Canal blockage can occur during the process of canal enlargement. Files are known to compact debris at the apex; even vital tissue can be compacted against the apical restriction. Suddenly, working length is shorter because the instruments are working against the packed mass at the apex.

Recognition: When the confirmed working length is no longer attained canal blockage is recognised. Evaluation radiographically will demonstrate the file is not reaching near the apical terminus.

Canal blockage corrections are accomplished by means of recapitulation and copious repeated irrigation. Starting with the smallest file used, the quarter turn technique using a chelating agent can be helpful.

8. Over or Underextended Root Canal Fillings

Root canal filling material is sometimes inadvertently extruded beyond the apical limit of the root canal, ending up in the periradicular bone, sinus or mandibular canal or even protruding through the cortical plate.

Inaccurately placed root canal filling usually takes place when a post-treatment radiograph is examined. Underextended filling is accomplished by re-treatment.

9. Vertical Root Fracture

A sudden crunching sound during obturation is a clear indication for the root fracture. This may occur during compaction of gutta-percha. It occur more often during lateral than vertical compaction.

Recognition: Sudden crunching sound, similar to that referred to as crepitus in the diseased temporo-mandibular joint, accompanied with pain reaction on the part of the patient, is a clear indicator that the root has fractured. It can be prevented by avoiding over preparation of the canal and the use of a passive, less forceful obturation technique and seating of posts.

10. Sodium hypochlorite accidents: Root Canal Failure

Sodium hypochlorite is the most popular and universally used agent but accidents are sometimes encountered and reported because of its extrusion beyond the apex.

Signs and symptoms mostly seen in NaOCl accidents are severe burning pain, progressively increasing moderate to severe widespread edema, profuse hemorrhage both through root canal and intersititially leading to bruising and echymosis.

No specific treatment can reverse the damages caused due to NaOCl. Mainstay of treatment is supportive including airway protection, control of swelling, pain relief and prevention of secondary infection. Patient should be reassured for the alarming swelling and pain. Copious irrigation with normal saline should be done. Cold compresses are placed initially for control of swelling. Pain control is achieved by NASIDs and opiod analgesics in severe pain. Prophylactic antibiotics therapy is essential.

The following steps can help clinicians avoid NaOCl accidents:

- Adequate access preparation

- Good working length control

- Irrigation needle placed 1 mm to 3 mm short of working length

- Needle placed passively and not locked in the canal

- Irrigant expressed into the root canal slowly

- Constant in and out movements of the irrigating needle into the canal space

- ‘Flowback’ of solution as it is expressed into the canal should be observed

- Use side delivery needles that are specifically designed for endodontic purpose

11. Tissue Emphysema

It is relatively uncommon but should not be overlooked. Two actions may cause tissue emphysema to happen – a blast of air to dry a canal or exhaust air from high-speed drill directed toward the tissue and not evacuated to the rear of the hand piece during apical surgery. The usual sequence of events is rapid swelling, erythema and crepitus.

Correction: Treatment recommended for tissue emphysema varies from palliative care and observation to immediate medical attention if the airway or mediastinum is compromised.

Contributed by:

Dr Yesh Sharma

Dr Sandeep Kaur Toor

Comments